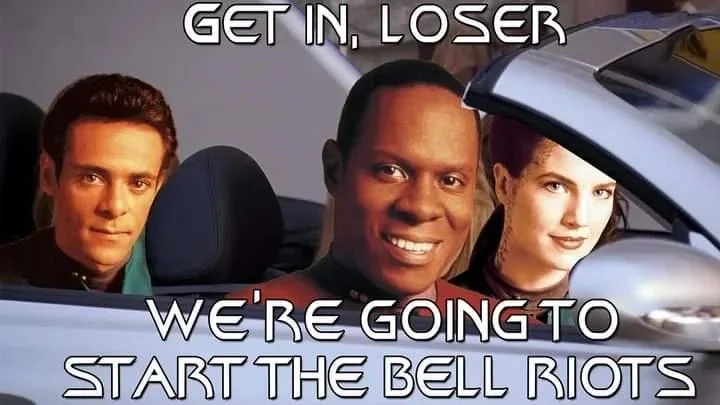

Happy Bell Riots to All Who Celebrate

Stay safe out there during one of the watershed events of the 21st century! I was going to write something about how the worst dystopia Star Trek could imagine in the mid-90s is dramatically, breathtakingly better than the future we actually got, but jwz has the roundup of people who already did.

Can you imagine the real San Franciso of 2024 setting aside a couple of blocks for homeless people to live? To hand out ration cards? For there to be infrastructure?

Like all good Science Fiction, Deep Space Nine doesn’t say a lot about the future, but it sure says an awful lot about the time in which it was written.

Why is this Happening, Part III: Investing in Shares of a Stairway to Heaven

We’ve talked a lot about “The AI” here at Icecano, mostly in terms ranging from “unflattering” to “extremely unflattering.” Which is why I’ve found myself stewing on this question the last few months: Why is this happening?

The easy answer is that, for starters, it’s a scam, a con. That goes hand-in-hand with it also being hype-fueled bubble, which is finally starting to show signs of deflating. We’re not quite at the “Matt Damon in Superbowl ads” phase yet, but I think we’re closer than not to the bubble popping.

Fad-tech bubbles are nothing new in the tech world, in recent memory we had similar grifts around the metaverse, blockchain & “web3”, “quantum”, self-driving cars. (And a whole lot of those bubbles all had the same people behind them as the current one around AI. Lots of the same datacenters full of GPUs, too!) I’m also old enough to remember similar bubbles around things like bittorrent, “4gl languages”, two or three cycles on VR, 3D TV.

This one has been different, though. There’s a viciousness to the boosters, a barely contained glee at the idea that this will put people out of work, which has been matched in intensity by the pushback. To put all that another way, when ELIZA came out, no one from MIT openly delighted at the idea that they were about to put all the therapists out of work.

But what is it about this one, though? Why did this ignite in a way that those others didn’t?

A sentiment I see a lot, as a response to AI skepticism, is to say something like “no no, this is real, it’s happening.” And the correct response to that is to say that, well, asbestos pajamas really didn’t catch fire, either. Then what happened? Just because AI is “real” it doesn’t mean it’s “good”. Those mesothelioma ads aren’t because asbestos wasn’t real.

(Again, these tend to be the same people who a few years back had a straight face when they said they were “bullish on bitcoin.”)

But I there’s another sentiment I see a lot that I think is standing behind that one: that this is the “last new tech we’ll see in our careers”. This tends to come from younger Xers & elder Millennials, folks who were just slightly too young to make it rich in the dot com boom, but old enough that they thought they were going to.

I think this one is interesting, because it illuminates part of how things have changed. From the late 70s through sometime in the 00s, new stuff showed up constantly, and more importantly, the new stuff was always better. There’s a joke from the 90s that goes like this: Two teams each developed a piece of software that didn’t run well enough on home computers. The first team spent months sweating blood, working around the clock to improve performance. The second team went and sat on a beach. Then, six months later, both teams bought new computers. And on those new machines, both systems ran great. So who did a better job? Who did a smarter job?

We all got absolutely hooked on the dopamine rush of new stuff, and it’s easy to see why; I mean, there were three extra verses of “We Didn’t Light the Fire” just in the 90s alone.

But a weird side effect is that as a culture of practitioners, we never really learned how to tell if the new thing was better than the old thing. This isn’t a new observation, Microsoft figured out to weaponize this early on as Fire And Motion. And I think this has really driven the software industry’s tendency towards “fad-oriented development,” we never built up a herd immunity to shiny new things.

A big part of this, of course, is that the press tech profoundly failed. A completely un-skeptical, overly gullible press that was infatuated shiny gadgets foisted a whole parade of con artists and scamtech on all of us, abdicating any duty they had to investigate accurately instead of just laundering press releases. The Professionally Surprised.

And for a long while, that was all okay, the occasional CueCat notwithstanding, because new stuff generally was better, and even if was only marginally better, there was often a lot of money to be made by jumping in early. Maybe not “private island” money, but at least “retire early to the foothills” money.

But then somewhere between the Dot Com Crash and the Great Recession, things slowed down. Those two events didn’t help much, but also somewhere in there “computers” plateaued at “pretty good”. Mobile kept the party going for a while, but then that slowed down too.

My Mom tells a story about being a teenager while the Beatles were around, and how she grew up in a world where every nine months pop music was reinvented, like clockwork. Then the Beatles broke up, the 70s hit, and that all stopped. And she’s pretty open about how much she misses that whole era; the heady “anything can happen” rush. I know the feeling.

If your whole identity and worldview about computers as a profession is wrapped up in diving into a Big New Thing every couple of years, it’s strange to have it settle down a little. To maintain. To have to assess. And so it’s easy to find yourself grasping for what the Next Thing is, to try and get back that feeling of the whole world constantly reinventing itself.

But missing the heyday of the PC boom isn’t the reason that AI took off. But it provides a pretty good set of excuses to cover the real reasons.

Is there a difference between “The AI” and “Robots?” I think, broadly, the answer is “no;” but they’re different lenses on the same idea. There is an interesting difference between “robot” (we built it to sit outside in the back seat of the spaceship and fix engines while getting shot at) and “the AI” (write my email for me), but that’s more about evolving stories about which is the stuff that sucks than a deep philosophical difference.

There’s a “creative” vs “mechanical” difference too. If we could build an artificial person like C-3PO I’m not sure that having it wash dishes would be the best or most appropriate possible use, but I like that as an example because, rounding to the nearest significant digit, that’s an activity no one enjoys, and as an activity it’s not exactly a hotbed of innovative new techniques. It’s the sort of chore it would be great if you could just hand off to someone. I joke this is one of the main reasons to have kids, so you can trick them into doing chores for you.

However, once “robots” went all-digital and became “the AI”, they started having access to this creative space instead of the physical-mechanical one, and the whole field backed into a moral hazard I’m not sure they noticed ahead of time.

There’s a world of difference between “better clone stamp in photoshop” and “look, we automatically made an entire website full of fake recipes to farm ad clicks”; and it turns out there’s this weird grifter class that can’t tell the difference.

Gesturing back at a century of science fiction thought experiments about robots, being able to make creative art of any kind was nearly always treated as an indicator that the robot wasn’t just “a robot.” I’ll single out Asimov’s Bicentennial Man as an early representative example—the titular robot learns how to make art, and this both causes the manufacturer to redesign future robots to prevent this happening again, and sets him on a path towards trying to be a “real person.”

We make fun of the Torment Nexus a lot, but it keeps happening—techbros keep misunderstanding the point behind the fiction they grew up on.

Unless I’m hugely misinformed, there isn’t a mass of people clamoring to wash dishes, kids don’t grow up fantasizing about a future in vacuuming. Conversely, it’s not like there’s a shortage of people who want to make a living writing, making art, doing journalism, being creative. The market is flooded with people desperate to make a living doing the fun part. So why did people who would never do that work decide that was the stuff that sucked and needed to be automated away?

So, finally: why?

I think there are several causes, all tangled.

These causes are adjacent to but not the same as the root causes of the greater enshittification—excuse me, “Platform Decay”—of the web. Nor are we talking about the largely orthogonal reasons why Facebook is full of old people being fooled by obvious AI glop. We’re interested in why the people making these AI tools are making them. Why they decided that this was the stuff that sucked.

First, we have this weird cultural stew where creative jobs are “desired” but not “desirable”. There’s a lot of cultural cachet around being a “creator” or having a “creative” jobs, but not a lot of respect for the people actually doing them. So you get the thing where people oppose the writer’s strike because they “need” a steady supply of TV, but the people who make it don’t deserve a living wage.

Graeber has a whole bit adjacent to this in Bullshit Jobs. Quoting the originating essay:

It's even clearer in the US, where Republicans have had remarkable success mobilizing resentment against school teachers, or auto workers (and not, significantly, against the school administrators or auto industry managers who actually cause the problems) for their supposedly bloated wages and benefits. It's as if they are being told ‘but you get to teach children! Or make cars! You get to have real jobs! And on top of that you have the nerve to also expect middle-class pensions and health care?’

“I made this” has cultural power. “I wrote a book,” “I made a movie,” are the sort of things you can say at a party that get people to perk up; “oh really? Tell me more!”

Add to this thirty-plus years of pressure to restructure public education around “STEM”, because those are the “real” and “valuable” skills that lead to “good jobs”, as if the only point of education was as a job training program. A very narrow job training program, because again, we need those TV shows but don’t care to support new people learning how to make them.

There’s always a class of people who think they should be able to buy anything; any skill someone else has acquired is something they should be able to purchase. This feels like a place I could put several paragraphs that use the word “neoliberalism” and then quote from Ayn Rand, The Incredibles, or Led Zeppelin lyrics depending on the vibe I was going for, but instead I’m just going to say “you know, the kind of people who only bought the Cliffs Notes, never the real book,” and trust you know what I mean. The kind of people who never learned the difference between “productivity hacks” and “cheating”.

The sort of people who only interact with books as a source of isolated nuggets of information, the kind of people who look at a pile of books and say something like “I wish I had access to all that information,” instead of “I want to read those.”

People who think money should count at least as much, if not more than, social skills or talent.

On top of all that, we have the financializtion of everything. Hobbies for their own sake are not acceptable, everything has to be a side hustle. How can I use this to make money? Why is this worth doing if I can’t do it well enough to sell it? Is there a bootcamp? A video tutorial? How fast can I start making money at this?

Finally, and critically, I think there’s a large mass of people working in software that don’t like their jobs and aren’t that great at them. I can’t speak for other industries first hand, but the tech world is full of folks who really don’t like their jobs, but they really like the money and being able to pretend they’re the masters of the universe.

All things considered, “making computers do things” is a pretty great gig. In the world of Professional Careers, software sits at the sweet spot of “amount you actually have to know & how much school you really need” vs “how much you get paid”.

I’ve said many times that I feel very fortunate that the thing I got super interested in when I was twelve happened to turn into a fully functional career when I hit my twenties. Not everyone gets that! And more importantly, there are a lot of people making those computers do things who didn’t get super interested in computers when they were twelve, because the thing they got super interested in doesn’t pay for a mortgage.

Look, if you need a good job, and maybe aren’t really interested in anything specific, or at least in anything that people will pay for, “computers”—or computer-adjacent—is a pretty sweet direction for your parents to point you. I’ve worked with more of these than I can count—developers, designers, architects, product people, project managers, middle managers—and most of them are perfectly fine people, doing a job they’re a little bored by, and then they go home and do something that they can actually self-actualize about. And I suspect this is true for a lot of “sit down inside email jobs,” that there’s a large mass of people who, in a just universe, their job would be “beach” or “guitar” or “games”, but instead they gotta help knock out front-end web code for a mid-list insurance company. Probably, most careers are like that, there’s the one accountant that loves it, and then a couple other guys counting down the hours until their band’s next unpaid gig.

But one of the things that makes computers stand out is that those accountants all had to get certified. The computer guys just needed a bootcamp and a couple weekends worth of video tutorials, and suddenly they get to put “Engineer” on their resume.

And let’s be honest: software should be creative, usually is marketed as such, but frequently isn’t. We like to talk about software development as if it’s nothing but innovation and “putting a dent in the universe”, but the real day-to-day is pulling another underwritten story off the backlog that claims to be easy but is going to take a whole week to write one more DTO, or web UI widget, or RESTful API that’s almost, but not quite, entirely unlike the last dozen of those. Another user-submitted bug caused by someone doing something stupid that the code that got written badly and shipped early couldn’t handle. Another change to government regulations that’s going to cause a remodel of the guts of this thing, which somehow manages to be a surprise despite the fact the law was passed before anyone in this meeting even started working here.

They don’t have time to learn how that regulation works, or why it changed, or how the data objects were supposed to happen, or what the right way to do that UI widget is—the story is only three points, get it out the door or our velocity will slip!—so they find someting they can copy, slap something together, write a test that passes, ship it. Move on to the next. Peel another one off the backlog. Keep that going. Forever.

And that also leads to this weird thing software has where everyone is just kind of bluffing everyone all the time, or at least until they can go look something up on stack overflow. No one really understands anything, just gotta keep the feature factory humming.

The people who actually like this stuff, who got into it because they liked making compteurs do things for their own sake keep finding ways to make it fun, or at least different. “Continuous Improvement,” we call it. Or, you know, they move on, leaving behind all those people whose twelve-year old selves would be horrified.

But then there’s the group that’s in the center of the Venn Diagram of everything above. All this mixes together, and in a certain kind of reduced-empathy individual, manifests as a fundamental disbelief in craft as a concept. Deep down, they really don’t believe expertise exists. That “expertise” and “bias” are synonyms. They look at people who are “good” at their jobs, who seem “satisfied” and are jealous of how well that person is executing the con.

Whatever they were into at twelve didn’t turn into a career, and they learned the wrong lesson from that. The kind of people who were in a band as a teenager and then spent the years since as a management consultant, and think the only problem with that is that they ever wanted to be in a band, instead of being mad that society has more open positions for management consultants than bass players.

They know which is the stuff that sucks: everything. None of this is the fun part; the fun part doesn’t even exist; that was a lie they believed as a kid. So they keep trying to build things where they don’t have to do their jobs anymore but still get paid gobs of money.

They dislike their jobs so much, they can’t believe anyone else likes theirs. They don’t believe expertise or skill is real, because they have none. They think everything is a con because thats what they do. Anything you can’t just buy must be a trick of some kind.

(Yeah, the trick is called “practice”.)

These aren’t people who think that critically about their own field, which is another thing that happens when you value STEM over everything else, and forget to teach people ethics and critical thinking.

Really, all they want to be are “Idea Guys”, tossing off half-baked concepts and surrounded by people they don’t have to respect and who wont talk back, who will figure out how to make a functional version of their ill-formed ramblings. That they can take credit for.

And this gets to the heart of whats so evil about the current crop of AI.

These aren’t tools built by the people who do the work to automate the boring parts of their own work; these are built by people who don’t value creative work at all and want to be rid of it.

As a point of comparison, the iPod was clearly made by people who listened to a lot of music and wanted a better way to do so. Apple has always been unique in the tech space in that it works more like a consumer electronics company, the vast majority of it’s products are clearly made by people who would themselves be an enthusiastic customer. In this field we talk about “eating your own dog-food” a lot, but if you’re writing a claims processing system for an insurance company, there’s only so far you can go. Making a better digital music player? That lets you think different.

But no: AI is all being built by people who don’t create, who resent having to create, who resent having to hire people who can create. Beyond even “I should be able to buy expertise” and into “I value this so little that I don’t even recognize this as a real skill”.

One of the first things these people tried to automate away was writing code—their own jobs. These people respect skill, expertise, craft so little that they don’t even respect their own. They dislike their jobs so much, and respect their own skills so little, that they can’t imagine that someone might not feel that way about their own.

A common pattern has been how surprised the techbros have been at the pushback. One of the funnier (in a laugh so you don’t cry way) sideshows is the way the techbros keep going “look, you don’t have to write anymore!” and every writer everywhere is all “ummmmm, I write because I like it, why would I want to stop” and then it just cuts back and forth between the two groups saying “what?” louder and angrier.

We’re really starting to pay for the fact that our civilization spent 20-plus years shoving kids that didn’t like programming into the career because it paid well and you could do it sitting down inside and didn’t have to be that great at it.

What future are they building for themselves? What future do they expect to live in, with this bold AI-powered utopia? Some vague middle-management “Idea Guy” economy, with the worst people in the world summoning books and art and movies out of thin air for no one to read or look at or watch, because everyone else is doing the same thing? A web full of AI slop made by and for robots trying to trick each other? Meanwhile the dishes are piling up? That’s the utopia?

I’m not sure they even know what they want, they just want to stop doing the stuff that sucks.

And I think that’s our way out of this.

What do we do?

For starters, AI Companies need to be regulated, preferably out of existence. There’s a flavor of libertarian-leaning engineer that likes to say things like “code is law,” but actually, turns out “law” is law. There’s whole swathes of this that we as a civilization should have no tolerance for; maybe not to a full Butlerian Jihad, but at least enough to send deepfakes back to the Abyss. We dealt with CFCs and asbestos, we can deal with this.

Education needs to be less STEM-focused. We need to carve out more career paths (not “jobs”, not “gigs”, “careers”) that have the benefits of tech but aren’t tech. And we need to furiously defend and expand spaces for creative work to flourish. And for that work to get paid.

But those are broad, society-wide changes. But what can those of us in the tech world actually do? How can we help solve these problems in our own little corners? We can we go into work tomorrow and actually do?

It’s on all of us in the tech world to make sure there’s less of the stuff that sucks.

We can’t do much about the lack of jobs for dance majors, but we can help make sure those people don’t stop believing in skill as a concept. Instead of assuming what we think sucks is what everyone thinks sucks, is there a way to make it not suck? Is there a way to find a person who doesn’t think it sucks? (And no, I don’t mean “Uber for writing my emails”) We gotta invite people in and make sure they see the fun part.

The actual practice of software has become deeply dehumanizing. None of what I just spent a week describing is the result of healthy people working in a field they enjoy, doing work they value. This is the challenge we have before us, how can we change course so that the tech industry doesn’t breed this. Those of us that got lucky at twelve need to find new ways to bring along the people who didn’t.

With that in mind, next Friday on Icecano we start a new series on growing better software.

Several people provided invaluable feedback on earlier iterations of this material; you all know who you are and thank you.

And as a final note, I’d like to personally apologize to the one person who I know for sure clicked Open in New Tab on every single link. Sorry man, they’re good tabs!

Why is this Happening, Part II: Letting Computers Do The Fun Part

Previously: Part I

Let’s leave the Stuff that Sucks aside for the moment, and ask a different question. Which Part is the Fun Part? What are we going to do with this time the robots have freed up for us?

It’s easy to get wrapped up in pointing at the parts of living that suck; especially when fantasizing about assigning work to C-3PO’s cousin. And it’s easy to spiral to a place where you just start waving your hands around at everything.

But even Bertie Wooster had things he enjoyed, that he occasionally got paid for, rather than let Jeeves work his jaw for him.

So it’s worth recalibrating for a moment: which are the fun parts?

As aggravating as it can be at times, I do actually like making computers do things. I like programming, I like designing software, I like building systems. I like finding clever solutions to problems. I got into this career on purpose. If it was fun all the time they wouldn’t have to call it “work”, but it’s fun a whole lot of the time.

I like writing (obviously.) For me, that dovetails pretty nicely with liking to design software; I’m generally the guy who ends up writing specs or design docs. It’s fun! I owned the customer-facing documentation several jobs back. It was fun!

I like to draw! I’m not great at it, but I’m also not trying to make a living out of it. I think having hobbies you enjoy but aren’t great at is a good thing. Not every skill needs to have a direct line to a career or a side hustle. Draw goofy robots to make your kids laugh! You don’t need to have to figure out a the monetization strategy.

In my “outside of work” life I think I know more writers and artists than programmers. For all of them, the work itself—the writing, the drawing, the music, making the movie—is the fun part. The parts they don’t like so well is the “figuring out how to get paid” part, or the dealing with printers part, or the weird contracts part. The hustle. Or, you know, the doing dishes, laundry, and vacuuming part. The “chores” part.

So every time I see a new “AI tool” release that writes text or generates images or makes video, I always as the same question:

Why would I let the computer do the fun part?

The writing is the fun part! The drawing pictures is the fun part! Writing the computer programs are the fun part! Why, why, are they trying to tell us that those are the parts that suck?

Why are the techbros trying to automate away the work people want to do?

It’s fun, and I worked hard to get good at it! Now they want me to let a robot do it?

Generative AI only seems impressive if you’ve never successfully created anything. Part of what makes “AI art” so enragingly radicalizing is the sight of someone whose never tried to create something before, never studied, never practiced, never put the time in, never really even thought about it, joylessly showing off their terrible AI slop they made and demanding to be treated as if they made it themselves, not that they used a tool built on the fruits of a million million stolen works.

Inspiration and plagiarism are not the same thing, the same way that “building a statistical model of word order probability from stuff we downloaded from the web” is not the same as “learning”. A plagiarism machine is not an artist.

But no, the really enraging part is watching these people show off this garbage realizing that these people can’t tell the difference. And AI art seems to be getting worse, AI pictures are getting easier spot, not harder, because of course it is, because the people making the systems don’t know what good is. And the culture is following: “it looks like AI made it” has become the exact opposite of a compliment. AI-generated glop is seen as tacky, low quality. And more importantly, seen as cheap, made by someone who wasn’t willing to spend any money on the real thing. Trying to pass off Krusty Burgers as their own cooking.

These are people with absolutely no taste, and I don’t mean people who don’t have a favorite Kurosawa film, I mean people who order a $50 steak well done and then drown it in A1 sauce. The kind of people who, deep down, don’t believe “good” is real. That it’s all just “marketing.”

The act of creation is inherently valuable; creation is an act that changes the creator as much as anyone. Writing things down isn’t just documentation, it’s a process that allows and enables the writer to discover what they think, explore how they actually feel.

“Having AI write that for you is like having a robot lift weights for you.”

AI writing is deeply dehumanizing, to both the person who prompted it and to the reader. There is so much weird stuff to unpack from someone saying, in what appears to be total sincerity, that they used AI to write a book. That the part they thought sucked was the fun part, the writing, and left their time free for… what? Marketing? Uploading metadata to Amazon? If you don’t want to write, why do you want people to call you a writer?

Why on earth would I want to read something the author couldn’t be bothered to write? Do these ghouls really just want the social credit for being “an artist”? Who are they trying to impress, what new parties do they think they’re going to get into because they have a self-published AI-written book with their name on it? Talk about participation trophies.

All the people I know in real life or follow on the feeds who use computers to do their thing but don’t consider themselves “computer people” have reacted with a strong and consistant full-body disgust. Personally, compared to all those past bubbles, this is the first tech I’ve ever encountered where my reaction was complete revulsion.

Meanwhile, many (not all) of the “computer people” in my orbit tend to be at-least AI curious, lots of hedging like “it’s useful in some cases” or “it’s inevitable” or full-blown enthusiasm.

One side, “absolutely not”, the other side, “well, mayyybe?” As a point of reference, this was the exact breakdown of how these same people reacted to blockchain and bitcoin.

One group looks at the other and sees people musing about if the face-eating leopard has some good points. The other group looks at the first and sees a bunch of neo-luddites. Of course, the correct reaction to that is “you’re absolutely correct, but not for the reasons you think.”

There’s a Douglas Adams bit that gets quoted a lot lately, which was printed in Salmon of Doubt but I think was around before that:

I’ve come up with a set of rules that describe our reactions to technologies:

Anything that is in the world when you’re born is normal and ordinary and is just a natural part of the way the world works.

Anything that’s invented between when you’re fifteen and thirty-five is new and exciting and revolutionary and you can probably get a career in it.

Anything invented after you’re thirty-five is against the natural order of things.

The better-read AI-grifters keep pointing at rule 3. But I keep thinking of the bit from Dirk Gently’s Detective Agency about the Electric Monk:

The Electric Monk was a labour-saving device, like a dishwasher or a video recorder. Dishwashers washed tedious dishes for you, thus saving you the bother of washing them yourself, video recorders watched tedious television for you, thus saving you the bother of looking at it yourself; Electric Monks believed things for you, thus saving you what was becoming an increasingly onerous task, that of believing all the things the world expected you to believe.

So, what are the people who own the Monks doing, then?

Let’s speak plainly for a moment—the tech industry has always had a certain…. ethical flexibility. The “things” in “move fast and break things” wasn’t talking about furniture or fancy vases, this isn’t just playing baseball inside the house. And this has been true for a long time, the Open Letter to Hobbyists was basically Gates complaining that other people’s theft was undermining the con he was running.

We all liked to pretend “disruption” was about finding “market inefficiencies” or whatever, but mostly what that meant was moving in to a market where the incumbents were regulated and labor had legal protection and finding a way to do business there while ignoring the rules. Only a psychopath thinks “having to pay employees” is an “inefficiency.”

Vast chunks of what it takes to make generative AI possible are already illegal or at least highly unethical. The Internet has always been governed by a sort of combination of gentleman’s agreements and pirate codes, and in the hunger for new training data, the AI companies have sucked up everything, copyright, licensing, and good neighborship be damned.

There’s some half-hearted attempts to combat AI via arguments that it violates copyright or open source licensing or other legal approach. And more power to them! Personally, I’m not really interested in the argument the AI training data violates contract law, because I care more about the fact that it’s deeply immoral. See that Vonnegut line about “those who devised means of getting paid enormously for committing crimes against which no laws had been passed.” Much like I think people who drive too fast in front of schools should get a ticket, sure, but I’m not opposed to that action because it was illegal, but because it was dangerous to the kids.

It’s been pointed out more than once that AI breaks the deal behind webcrawlers and search—search engines are allowed to suck up everyone’s content in exchange for sending traffic their way. But AI just takes and regurgitates, without sharing the traffic, or even the credit. It’s the AI Search Doomsday Cult. Even Uber didn’t try to put car manufacturers out of business.

But beyond all that, making things is fun! Making things for other people is fun! It’s about making a connection between people, not about formal correctness or commercial viability. And then you see those terrible google fan letter ads at the olympics, or see people crowing that they used AI to generate a kids book for their children, and you wonder, how can these people have so little regard for their audience that they don’t want to make the connection themselves? That they’d rather give their kids something a jumped-up spreadsheet full of stolen words barfed out instead of something they made themselves? Why pass on the fun part, just so you can take credit for something thoughtless and tacky? The AI ads want you to believe that you need their help to find “the right word”; what thay don’t tell you is that no you don’t, what you need to do is have fun finding your word.

Robots turned out to be hard. Actually, properly hard. You can read these papers by computer researchers in the fifties where they’re pretty sure Threepio-style robot butlers are only 20 years away, which seems laughable now. Robots are the kind of hard where the more we learn the harder they seem.

As an example: Doctor Who in the early 80s added a robot character who was played by the prototype of an actual robot. This went about as poorly as you might imagine. That’s impossible to imagine now, no producer would risk their production on a homemade robot today, matter how impressive the demo was. You want a thing that looks like Threepio walking around and talking with a voice like a Transformer? Put a guy in a suit. Actors are much easier to work with. Even though they have a union.

Similarly, “General AI” in the HAL/KITT/Threepio sense has been permanently 20 years in the future for at least 70 years now. The AI class I took in the 90s was essentially a survey of things that hadn’t worked, and ended with a kind of shrug and “maybe another 20?”

Humans are really, really good at seeing faces in things, and finding patterns that aren’t there. Any halfway decent professional programmer can whip up an ELIZA clone in an afternoon, and even knowing how the trick works it “feels” smarter than it is. A lot of AI research projects are like that, a sleight-of-hand trick that depends on doing a lot of math quickly and on the human capacity to anthropomorphize. And then the self-described brightest minds of our generation fail the mirror test over and over.

Actually building a thing that can “think”? Increasingly seems impossible.

You know what’s easy, though, comparatively speaking? Building a statistical model of all the text you can pull off the web.

On Friday: conclusions, such as they are.

Why is this Happening, Part I: The Stuff That Sucks

When I was a kid, I had this book called The Star Wars Book of Robots. It was a classic early-80s kids pop-science book; kids are into robots, so let’s have a book talking about what kinds of robots existed at the time, and then what kinds of robots might exist in the future. At the time, Star Wars was the spoonful of sugar to help education go down, so every page talked about a different kind of robot, and then the illustration was a painting of that kind of robot going about its day while C-3PO, R2-D2, and occasionally someone in 1970s leisureware looked on. So you’d have one of those car factory robot arms putting a sedan together while the droids stood off to the side with a sort of “when is Uncle Larry finally going to retire?” energy.

The image from that book that has stuck with me for four decades is the one at the top of this page: Threepio, trying to do the dishes while vacuuming, and having the situation go full slapstick. (As a kid, I was really worried that the soap suds were going to get into his bare midriff there and cause electrical damage, which should be all you need to know to guess exactly what kind of kid I was at 6.)

Nearly all the examples in the book were of some kind of physical labor; delivering mail, welding cars together, doing the dishes, going to physically hostile places. And at the time, this was the standard pop-culture job for robots “in the future”, that robots and robotic automation were fundamentally physical, and were about relieving humans from mechanical labor.

The message is clear: in the not to distant future we’re all going to have some kind of robotic butler or maid or handyman around the house, and that robot is going to do all the Stuff That Sucks. Dishes, chores, laundry, assorted car assembly, whatever it is you don’t want to do, the robot will handle for you.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot over the last year and change since “Generative AI” became a phrase we were all forced to learn. And what’s interesting to me is the way that the sales pitch has evolved around which is the stuff that sucks.

Robots, as a storytelling construct, have always been a thematically rich metaphor in this regard, and provide an interesting social diagnostic. You can tell a lot about what a society thinks is “the stuff that sucks” by looking at both what the robots and the people around them are doing. The work that brought us the word “robot” itself represented them as artificially constructed laborers who revolted against their creators.

Asimov’s body of work, which was the first to treat robots as something industrial and coined the term “robotics” mostly represented them as doing manual labor in places too dangerous for humans while the humans sat around doing science or supervision. But Asimov’s robots also were always shown to be smarter and more individualistic than the humans believed, and generally found a way to do what they wanted to do, regardless of the restrictions from the “Laws of Robotics.”

Even in Star Wars, which buries the political content low in the mix, it’s the droids where the dark satire from THX-1138 pokes through; robots are there as a permanent servant class doing dangerous work either on the outside of spaceships or translating for crime bosses, are the only group shown to be discriminated against, and have otherwise unambiguous “good guys” ordering mind wipes of, despite consistently being some of the smartest and most capable characters.

And then, you know, Blade Runner.

There’s a lot of social anxiety wrapped up in all this. Post-industrial revolution, the expanding middle classes wanted the same kinds of servants and “domestic staff” as the upper classes had. Wouldn’t it be nice to have a butler, a valet, some “staff?” That you didn’t have to worry about?

This is the era of Jeeves & Wooster, and who wouldn’t want a “gentleman’s gentleman” to do the work around the house, make you a hangover cure, drive the car, get you out of scrapes, all while you frittered your time away with idiot friends?

(Of course, I’m sure it’s a total coincidence this is also the period where the Marxists & Socialist thinkers really got going.)

But that stayed asperational, rather than possible, and especially post-World War II, the culture landed on sending women back home and depending on the stay-at-home mom handle “all that.”

There’s a lot of “robot butlers” in mid-century fiction, because how nice would it be if you could just go to the store and buy that robot from The Jetsons, free from any guilt? There’s a lot to unpack there, but that desire for a guilt-free servant class was, and is, persistant in fiction.

Somewhere along the lines, this changes, and robots stop being manual labor or the domestic staff, and start being secretaries, executive assistants. For example, by the time Star Trek: The Next Generation rolls around in the mid-80s, part of the fully automated luxury space communism of the Federation is that the Enterprise computer is basically the perfect secretary—making calls, taking dictation, and doing research. Even by the then it was clear that there was a whole lot of “stuff to know”, and so robots find themselves acting as research assistants. Partly, this is a narrative accelerant—having the Shakespearian actor able to ask thin air for the next plot point helps move things along pretty fast—but the anxiety about information overload was there, even then. Imagine if you could just ask somebody to look it up for you! (Star Trek as a whole is an endless Torment Nexus factory, but that’s a whole other story.)

I’ve been reading a book about the history of keyboards, and one of the more intersting side stories is the way “typing” has interacted with gender roles over the last century. For most of the 1900s, “typing” was a woman’s job, and men, who were of course the bosses, didn’t have time for that sort of tediousness. They’re Idea Guys, and the stuff that sucks is wrestling with an actual typewriter to write them down.

So, they would either handwrite things they needed typed and send it down to the “typing pool”, or dictate to a secretary, who would type it up. Typing becomes a viable job out of the house for younger or unmarried women, albeit one without an actual career path.

This arrangement lasted well into the 80s, and up until then the only men who typed themselves were either writers or nerds. Then computers happened, PCs landed on men’s desks, and it turns out the only thing more powerful than sexism was the desire to cut costs, so men found themselves typing their own emails. (Although, this transition spawns the most unwittingly enlightening quote in the whole book, where someone who was an executive at the time of the transition says it didn’t really matter, because “Feminism ruined everything fun about having a secretary”. pikachu shocked face dot gif)

But we have a pattern; work that would have been done by servants gets handed off to women, and then back to men, and then fiction starts showing up fantasizing about giving that work to a robot, who won’t complain, or have an opinion—or start a union.

Meanwhile, in parallel with all this “chat bots” have been cooking along for as long as there have been computers. Typing at a computer and getting a human-like response was an obvious interface, and spawned a whole set of thought similar but adjacent to all those physical robots. ELIZA emerged almost as soon as computers were able to support such a thing. The Turing test assumes a chat interface. “Software Agents” become a viable area of research. The Infocom text adventure parser came out of the MIT AI lab. What if your secretary was just a page of text on your screen?

One of the ways that thread evolved emerged as LLMs and “Generative AI”. And thanks to the amount of VC being poured in, we get the last couple of years of AI slop. And also a hype cycle that says that any tech company that doesn’t go all-in on “the AI” is going to be left in the dust. It’s the Next Big Thing!

Flash forward to Apple’s Worldwide Developer Conference earlier this summer. The Discourse going into WWDC was that Apple was “behind on AI” and needed to catch up to the industry, although does it really count as behind if all your competitors are up over their skis? And so far AI has been extremely unprofitable, and if anything, Apple is a company that only ships products it knows it can make money on.

The result was that they rolled out the most comprehensive vision of how a Gen AI–powered product suite looks here in 2024. In many ways, “Apple Intelligence” was Apple doing what they do best—namely, doing their market research via letting their erstwhile competitors skid into a ditch, and then slide in with a full Second Mover Advantage by saying “so, now do you want something that works?”

They’re very, very good at identifying The Stuff That Sucks, and announcing that they have a solution. So what stuff was it? Writing text, sending pictures, communicating with other people. All done by a faceless, neutral, “assistant,” who you didn’t have to engage with like they were a person, just a fancy piece of software. Computer! Tea, Earl Gray! Hot!

I’m writing about a marketing event from months ago because watching their giant infomercial was where something clicked for me. They spent an hour talking about speed, “look how much faster you can do stuff!” “You don’t have to write your own text, draw your own pictures, send your own emails, interact directly with anyone!”

Left unsaid was what you were saving all that time for. Critically, they didn’t annouce they were going to a 4-day work week or 6-hour days, all this AI was so people could do more “real work”. Except that the “stuff that sucks” was… that work? What’s the vision of what we’ll be doing when we’ve handed off all this stuff that sucks?

Who is building this stuff? What future do they expect to live in, with this bold AI-powered economy? What are we saving all this time for? What future do these people want? Why are these the things they have decided suck?

I was struck, not for the first time, by what a weird dystopia we find ourselves in: “we gutted public education and non-STEM subjects like writing and drawing, and everyone is so overworked they need a secretary but can’t afford one, so here’s a robot!”

To sharpen the point: why in the fuck am I here doing the dishes myself while a bunch of techbros raise billions of dollars to automate the art and poetry? What happened to Threepio up there? Why is this the AI that’s happening?

On Wednesday, we start kicking over rocks to find an answer...

There we go: Harris/Walz 24

Candidate swap complete. Okay, I’m convinced. Let’s go win this thing.

The party conventions are always a sales event—they’re the political versions of those big keynotes Apple does—but this one was remarkably well put-together, probably the best of my lifetime, which is especially insane considering they had to swap candidates only four weeks ago. I’m acting like Belle’s father from Beauty and the Beast, just staring at it asking “how is this accomplished?” I’m really looking forward to next summer’s deluge of tell-all behind-the-scenes books, explaining how in the heck they pulled any of this off.

This bit from Josh Marshall’s piece on the final night stuck with me:

What I took from this is a sense of focus and discipline from the people running Harris’ convention and campaign — not getting lost in glitz or stagecraft but defining a specific list of critical deliverables and then methodically checking them off the list. This was going on in the midst of what was unquestionably a high-powered and high-energy event. There was a mix of discipline and ability there that could not fail to have an impact but was also, in the intensity of the final day of a convention, easy to miss.

The other nights had some of this too. But it came through to me most clearly tonight.

I continue to think there’s more going on in this campaign than much of the political and commenting class has yet understood or reckoned with.

There’s a thing going on here that’s not just a “honeymoon phase” after a surprise switch-up. Personally, I think a big part is the Dem’s long overdue embrace of being the “regular people” party, but critically, without a self-destructive “pivot to the center.” In the US “The Center”, like “libertarian” is just a code word for a republican who smokes weed and doesn’t openly hate the gays. For ages now the Dems have surrendered so much American iconography—camo, flags, guns, the entire midwest—and it’s incredibly refreshing to see the Dems openly embrace all that “Real America” stuff, leaving the Repubs with nothing but looking like the creepy weirdo loosers they are.

I tend to think of the Democrats as, effectively, a British-style coalition, just without the framework the parliamentary system provides of actually having each member party having a public number of seats. Instead the factions are fluid and more obscure. Which makes intra-party negotiations hard even in better times, and even more so when the “other side” isn’t a coalition and is full of wannabe petty dictators. From the outside, and probably from the inside, it’s hard to tell how the various factions are doing versus each other.

There are, bluntly, a lot of issues that just aren’t on the ballot this year, which for whatever reason have fallen outside of the contextual Overton window of the ’24 election. The lack of formal coalition dynamics makes those so frustrating; there’s no way to know how close they were to being on the ballot. And, of course, the reason I keep calling this a “harm reduction” election is that for those about six things I’m subtweeting, the other side would be an absolute catastrophe. And that’s before we remember that the baseline of the opponents here really is “…or fascism.”

That said, it’s such a relief to see that the party seems to have finally shook off the Clinton/Blair era “Third Way” hangover and landed in a much more progressive place than I’d have ever hoped a few years ago. This feels like a group that would have held the banks accountable, for starters?

The first Bill Clinton campaign is the one this keeps making me think of, that explicit sense of “the old ways failed, here comes the new generation.” (Speaking of, can you imagine how hard Harris would kill on the old Arsenio show? For that matter, how hard Walz would?)

But more than any of that, this is a campaign and a candiate that’s here to play None of this gingerly hoping “we can finally talk about policy,” this a group that’s solidly on the offensive and staying there. The Dem’s traditional move has been to blow what should have been easy wins (looking at you 2000 and 2016) mostly by wrecking out the campaign to chase votes they were never going to get, or because actually trying to win power was beneath them somehow. Not this time. Non-MAGA America is deeply, profoundly sick of those assholes, and Harris has really captured the desire to move on as a country.

Finally!

In any case, we’re really though the looking glass now. No one has any idea what’s going to happen. Yeah, I saw that poll, and yes that one, and that one. We’re so far outside the lines I don’t think any of those mean anything we can interpret with the data we have. At this point, anybody who says what they think is going to happen without ending the sentence with a question mark is lying.

To quote Doctor Who: “Oh, knowing's easy. Everyone does that ad nauseam. I just sort of hope."

Further Exciting Consulting Opportunitues

I am expanding the offerings of my consulting company,we now offer a second service, which is this:

When someone is making, say, an eight season of a tv show for a streaming service, they can come to me and tell me what events will take place in those eight episodes. And then I will say,

“That is four episodes, max. What do ya got lying around that you’re saving for the second season? Let’s jam that in there too.”

“White Guy Tacos”

I just want to say that as a white guy with laughably-low spice tolerance, I never expected my demographic to be represented in a major national election, much less dominate a news cycle?

This is our time, fellow spice-phobes! You love to see it.

Feature Request: I Already Know That Part, Siri

I live pretty close to a major interstate highway. If you stand in the right place in my backyard, you can see the trucks! But, thanks to the turn-of-the-century suburb I live in, it’s at least 5 “turns” to get from my house to the freeway. I also live in one of those cities that’s a major freeway confluence, which means I’m another 2 or 3 “turns” away from at least 5 different numbered freeways?

So of course, when I need directions from Apple Maps (or any other nav system,) Siri very patiently explains how to get from my house to the freeway, which, yes Siri, I know that part.

I wish there was a way to mark an area on the the map as “look, I grew up here, I got this.” I wish, when I’m driving out to the mountains or whatever, Siri would start with “Get on I-5 south, I’ll be back with you in half an hour.” I want to be able to tell it “no, look, I know all these turns, I just want you to tell me when we’re at the destination so I don’t drive past the weird driveway again.” That’s an Apple Intelligence feature I’d be impressed by.

This Adam Savage Video

The YouTube algorithm has decided that what I really want to watch are Adam Savage videos, and it turns out the robots are occasionally right? So, I’d like to draw your attention to this vid where Adam answers some user questions: Were Any Myths Deemed Too Simple to Test on MythBusters?

It quickly veers moderately off-topic, and gets into a the weeds on what kinds of topics MythBusters tackled and why. You should go watch it, but the upshot is that MythBusters never wanted to invite someone on just to make them look bad or do a gotcha, so there was a whole class of “debunking” topics they didn’t have a way in on; the example Adam cites is dowsing, because there’s no way to do an episode busting dowsing without having a dowser on to debunk.

And this instantly made clear to me why I loved MythBusters but couldn’t stand Penn & Teller’s Bullshit!. The P&T Show was pretty much an extended exercise in “Look at this Asshole”, and was usually happy to stop there. MythBusters was never interested in looking at assholes.

And, speaking of Adam Savage, did I ever link to the new Bobby Fingers?

This is relevant because it’s a collaboration with Adam Savage, and the Slow Mo Guys, who also posted their own videos on the topic:

Shooting Ballistic Gel Birds at Silicone Fabio with @bobbyfingers and @theslowmoguys!

75mph Bird to the Face with Adam Savage (@tested) and @bobbyfingers - The Slow Mo Guys

It’s like a youtube channel Rashomon, it’s great.

On Enthusiasm

Remember Howard Dean? Ran for president in 2004. Had huge grassroots support, got “the kids” really excited, and then got too excited in public, and went home to let Kerry lose the election.

I always thought the media kerfluffle around the “Dean Scream” was bizarre. Years later I saw a documentary where he was interviewed, about the election and other things, and he came across as sane, thoughtful, charismatic. Afterwards, he was a tremendously successful head of the nation party apparatus. Towards the end, the interviewer asked him if he’d do “the scream”, and he refused. Seemed embarrassed by the idea, kinda pissed the interviewer would bring it up. Oh, I thought, this is why you lost the election. You have a brief moment of actual personality in public, it’s still the thing you’re the most known for, and even now you can’t bring yourself to embrace it.

The Dems, at least for the last 20–30 years, have had a strange aversion to “enthusiasm”, treating it as somehow low-class or embarrassing. I guess this partly their self-identity as the “adults in the room,” and partly a reaction to looking over at Reagan and saying “screaming crowds are the thing the other guys do”.

So the guy in ’04 who has the kids all excited allows the media to shame him out of the race for being excited. And clearly he was actually embarrassed, based on that interview. He should have leaned into it, made that his thing. Opened every event with that yell, get a call and response going. Instead, nope, we’re gonna let the most boring man in the world lose the election to the war criminal running on ending social security.

And of course, the really maddeningly weird thing is that the Dem base is much more purpose-driven, more emotionally-connected to outcomes. They’re the ones who will stay home unless you fire them up! The main opponent has always been apathy!

So the Dems that win are (mostly) charismatic outsiders, whereas the party wants to run “grownups.” So you have Gore, who runs basically as a robot, and then as soon as he loses shows up on Futurama and is incredibly funny. Remember how scandalized the other Dems were by Clinton playing the sax on Arsenio? I think this was one of the dynamics that fueled the Bernie-Clinton feud too; somehow the Dems though people yelling “Bernie or bust” meant he wasn’t electable?

I suspect this is mostly a generational thing. The batch of boomer-age Dems that have been running the show the last 30 years have always treated “people being excited” as not grown up enough. And fair enough, if you grew up in the 50s & 60s, there was a very, very limited number of things you were allowed to “like” or express feeling about; maybe sports? Otherwise, stoicism was the goal. Maybe because an entire generation grew up with parents who had undiagnosed PTSD?

The younger generations aren’t like that? Or at the very least, have a different set of “things you’re allowed to be excited about” and aren’t fundamentally embarrassed by the concept of “excitement” or “emoting”. So those people start being in charge, and they’re like, no actually, stoicism isn’t the goal, let’s get the base fired up. Which turns out to be really valuable when the opponent isn’t “the other guy” but “staying home”?

Anyway, my Hot Take is that Harris/Walz is what you get when the Dems stop treating “enthusiasm” as something low class and embarrassing.

More than anything, Biden had a vibes problem; I see that Harris is now polling ahead of the convicted felon/ failed businessperson on “the economy”, as opposed to Biden who was well behind. It’s the same economy! Same administration! Same failed casinos! Vibes issue.

Being “the grown ups” meant being reactive, trying to stick to “serious topics”, with the result being that the other side gets to dictate the terms of the fight and then ground you down over a year(s)-long campaign.

But now we’ve got a team actually trying to fire up the base, setting the terms, taking the initiative. Part of why “mind you own damn business” has popped so hard as a campaign theme is that this is the kind of topic everyone actually cares about and has wanted a Dem to run on since forever, instead of the finer points of NATO funding or whatever.

This really does feel like a campaign run by people who at a critical age, instead of watching Mr Smith goes to Washington, watched Heathers. As they say, let’s not go back.

Apple vs Games

Apple Arcade is in the news again, for not great reasons; as always, Tsai has the roundup, the but the short, short version is that Arcade is going exactly as well as all of Apple’s other video game–related efforts have gone for the last “since forever.”

My first take was that games might be the most notable place Apple’s “one guy at the top” structure falls down. Apple’s greatest strength and greatest weakness has always been that the whole company is laser focused on whatever the guy in charge cares about, and not much of anything else. Currently, that means that Apple’s priorities are, in no particular order, privacy, health, thin devices, operational efficiency, and, I guess, becoming “the new HBO.” Games aren’t anywhere near that list, and never have been. I understand the desire to keep everything flowing through one central point, and not to have siloed-off business units or what have you. On the other hand Bill Gates wasn’t a gamer either, but he knew to hire someone to be in charge of X-everything and leave them alone.

But then I remembered AppleTV+. Somehow, in a very short amount of time, Apple figured out how to be a production company, and made Ted Lasso, a new Fraggle Rock, some new Peanuts, and knocked out a Werner Herzog documentary for good measure. I refuse to believe that happened because Tim Apple was signing off on every production decision or script; they found the right people and enabled them correctly.

At this point, there’s just no excuse why AppleTV has something like Ted Lasso, and Apple Arcade doesn’t. There’s obvious questions like “why did I play Untitled Goose Game on my Switch instead of my Mac” and “why did they blow acquiring Bungie twice”. Why isn’t the Mac the premier game platform? Why? What’s the malfunction?

Meet the Veep

And there we go, it’s Walz. Personally, I was hoping for Mayor Pete, but as Elizabeth Sandifer says: “…when you create the campaign's new messaging strategy you get to be the VP nom.". I love that he’s a regular guy in the way that’s the exact opposite of what we use the word “weird” as a shorthand for.

The Dems claiming the title of the party of regular, normal, non-crazy people is long overdue; this is a note they should have been playing since at least the Tea Party, and probably since Gingrich. But, like planting a tree, the second best time is now, and Walz’s midwestern cool dad energy is the perfect counterpoint to the Couch Experience.

“Both sides are the same” is right-wing propganda designed to reduce voter turnout, but the Dems don’t always run a ticket that makes it easy to dispute. What I like about the Harris/Walz vs Trump/Vance race is that the differences are clear, even at a distance. What future do you want, America?

As I keep saying, this is a “turn out the base” election; everyone already knows which side they’d vote for, and the trick is to get them to think it’s worth it to bother to vote. Each candidate is running against apathy, not each other. Fairly or not, over the summer the Democrats found themselves with a substantial enthusiasm gap. The Repubs didn’t have a huge amount of enthusiasm either, but the reality is the members of the Republican coalition are more likely to show up and vote for someone they don’t like than the Dems, so structurally thats the sort of thing that hurts Team Blue more.

Literally no one wanted to do the 2020 election over again, and in one of those bizarre unfair moments America decided to blame Biden for it, instead of blaming the guy who lost for not staying down. But more than that, complaining about how “old” everyone was also a shorthand for something else—all the actors here are people who’ve been around since the 80s. We just keep re-litigating the ghosts of the 20th century. Obama felt like the moment we were finally done having elections rooted in how the Boomers felt about Nixon, but then, no, another three cycles made up entirely of people who’ve been household names since Cheers was on the air.

And then Harris crashes into the race at the last second with an “oh yeaaahhhh!” Suddenly, we’ve got something new. This finally feels like not just a properly post-Obama ticket, but actually post “The Third Way”; both in terms of policy and attitude this is the campaign the Dems should have been running every election in the 21st century. And for once, the Dems aren’t just trying to score points with some hypothetical ref and win on technicals, they’re here to actually win. Finally.

I’m as surprised as anyone at the amount of excitement that’s built up over the last two weeks; I was sure swapping candidates was an own-goal for the ages, but now I’m sure I was wrong.

Rooting for the winning team is fun, and the team with the initiative and hustle is usually the one that wins. It’s self-perpetuating, in both directions. (This is a big part of how Trump managed to stumble into a win in ’16, it was a weird feedback loop of him doing something insane and then everyone else going “hahaha what” and all that kept building on itself until he was suddenly the President.)

Accurately or not, the Dems had talked themselves into believing they were going to lose, and were acting like it. Now, not so much! The feedback loops are building the other way, and as Harris keeps picking up more support, you can see the air bleeding out of Trump’s tires as his support drifts away because he’s only fun when he’s winning.

I have a conceptual model that I use for US Presidential elections that has very rarely let me down. It goes like this: every cycle the Republicans run someone who reads as a Boss, and the Democrats run someone who reads as a college Professor. And so most elections turn into a contest between the worst boss you’ve ever had against your least favorite teacher; with the final decision boiling down to, basically, “would you rather work for this guy or take a class from that guy”. (Often leading to a frustrated “bleah, neither!”)

And elections pretty consistently go to the team that wins that comparison. As a historical example, I liked Gore a lot, but he really had the quality that he’d grade you down on a paper because he thought you used an em dash wrong when you didn’t, whereas W (war crimes notwithstanding) seemed like the kind of boss that wouldn’t hassle you too bad and would throw a great summer BBQ. And occasionally one side or the other pops a good one—Obama seemed like he’d be your favorite law professor of all time.

Viewing this ticket via that lens? This one I like. We have the worst boss you can imagine running with the worst coworker you’ve ever had, against literally the cool geography teacher/football coach and the lady that seems like she’d be your new favorite professor? Hell yeah. I’m sold. Let’s do this.

Retweeting Feeds

There’s a feature I miss from the old twitter, or rather, there’s a use case that twitter filled better than anything else.

The use case is this: RSS feeds are a great way to publish content, but that’s where it stops—there’s no intrinsic way to (re)share an item from a feed you’re subscribed to with anyone else, to retweet it, if you will. I’d love to have an easy way to reshare content from feeds I’m subscribed to.

I think one of the reasons that twitter sucked the air out of the RSS ecosystem was that not only was it trivial to set up a twitter account that worked just like an RSS feed, with links to your blog or podcast or whatever, but everyone who followed your feed could re-share it with their followers with a single action, optionally adding a comment. I cannot tell you how much great stuff I found out about because someone I followed on twitter quote-tweeted it.

Here in the post-twitter afterscape, I keep wishing NetNewsWire had a retweet button. I’ve spent enough time in product design and development to know why that doesn’t exist; something that could re-share an item from an RSS feed out into a new feed with a connection back to the original feed requires about 80% of twitter, if you’re going to build all that, add the ability to post your own content as well and go all the way to a social network/microblogging system/twitter clone. And I guess the solution is either bluesky or mastodon.

But I keep thinking there has to be something between turn of the century–style RSS feeds and a full-blown social network. And I am putting this out in the universe because I absolutely do not want to build or work on this myself, I want to use it. (All my actual startup ideas are going to be buried with me.)

Somebody go figure this out!

Edited to add: I am reminded by an Alert Reader that Google Reader (RIP) had a similar feature, you could “share” things from your feed. But google’s gonna google and the share list was basically your gmail contacts list? Which would lead to some really bizarre results like suddenly seeing a thing in your feed that got there because a friend of a friend shared it, because you were both on the same party invite a couple of years ago. Cool idea, but again, something twitter improved on by making those connections obvious.

Anyone Else Remember This Giant Maze Thing?

I have this vague memory that floats up into my mind every couple of years. There was this amusement park that was just a giant, human-scale maze. I remember the walls being basically plywood fencing? I think it was in the Bay Area, or at least “in that direction” from the central valley. This would have been 1990-ish?

I never went, but I think we drove by it a few times? There were a bunch of TV commercials, which I was sort of fascinated by. What I mostly remember is that they had a mascot that I thought looked exactly like The Noid from Domino’s Pizza, and in the low-information environment of the world before the web, I was confused about if this place was now both a bad pizza place and a maze?

Anyone else remember any of this?

…

Anyway, this bubbled back up again this week, and I decided to finally figure out what the heck I was remembering. I’m gonna put some space so you can see if you can remember any of this before you scroll down.

.

..

…

….

It was a real thing!

It was called The Wooz.

Opened in 1988, closed in ’92, it was in Vacaville, basically across the freeway from where the Nut Tree used to be, adjacent to that whole outlet store cluster that was going to be the future of retail back before the Roseville Gallaria opened up. Apparently mazes were a fad in Japan in the late 80s, sort of the Escape Rooms of theirtime, and so someone tried to expand that out to North America.

The idea isn’t great on it’s own, but why Vacaville? I guess they picked it because of that outlet mall thing, but let’s talk about your competition. Ignoring that you’re only a couple hours away from Disneyland, at the time you’re less than an hour away from the pre-Six Flags Marine World, Great America, and even the old Waterworld USA at Cal Expo. Hell, there’s even two Scandias in range. A big maze with no shade made out of redwood fencing is a hard sell, even without that many rides nearby?

Some links for you!

The history of the hottest, most ill-advised theme park ever made: The Wooz

The Wooz - Vacaville - LocalWiki

Do not sleep on the embedded video in that first link, an episode of the That’s Incredible Show on the park which includes a race through the maze, one of the participants of which was Steve Wozniak, who is introduced only as “a computer whiz”. I love, love, love that there was about a 5-year window where “co-founder of Apple Computer” was not something to be proud of, of which 1989 was the absolute peak. He’s basically here because he was a minor local celebrity. Presumably he got the call after Cal Worthington (and his dog spot) turned them down?

And the mascot did look an awful lot like the Noid.

Pretty Weird

Absolutely loving this new Gen-X energy the Dems have suddenly discovered by just pointing out that the Repubs are super weird.

And they are! The republican party has been an absolute freakshow since at least the Gingrich era, and certainly since those tea party assholes. I distinctly remember wishing that Gore had run on a platform of “look how weird these guys are” and W looks positively sane next to the current freak farm. Normal people don’t actually care what goes on in other people’s bathrooms, houses, or pants?

This has completely thrown the repubs for a loop. I see they’re basically trying a Pee-Wee Herman “I know you are but what am I” move by trial-balooning various flavors of “we’re not weird, you the ones with ____” with various totally normal things in that blank spot, with a side-order of “weird is what all the bullies called me, who then is the real bully” crap.

The past couple of decades have tought the repubs that saying things like “ahh, who is the real villan” or “but you participate in society, interesting” or “then you are no better than they” is the equivalent of the roadrunner painting a fake tunnel on the side of a mountain, and that the dems will reliably run right into it, Wile E. Coyote–style.

So it is incredibly refreshing to see that the dems have finally discovered the correct response, which is “shut the fuck up, you freaky weirdo!”

Because everyone who has actually lived a life knows there is a difference between weird (kid plays too much D&D) and weird (do not, under any circumstances, leave your drink uncovered near him).

This election, more than usual, is everyone in that first group vs everyone in the second.

Cognitive Surplus

I finally dug up a piece I that has been living rent-free in my head for sixteen years:

Gin, Television, and Social Surplus - Here Comes Everybody:

I was recently reminded of some reading I did in college, way back in the last century, by a British historian arguing that the critical technology, for the early phase of the industrial revolution, was gin.

The transformation from rural to urban life was so sudden, and so wrenching, that the only thing society could do to manage was to drink itself into a stupor for a generation. The stories from that era are amazing--there were gin pushcarts working their way through the streets of London.

...

This was a talk Clay Shirky gave in 2008, and the transcript lived on his website for a long time but eventually rotted away. I stumbled across an old bookmark the other day, and realized I could use that to dig it out of the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, so here we are!

A couple years later, Shirky turned this talk into a full book called Cognitive Surplus: How Technology Makes Consumers into Collaborators, which is presumably why the prototype vanished off his website. The book is okay, but it’s a classic example of an idea that really only needs about 20 pages at the most getting blown out to 200 because there’s a market for “books”, but not “long blog posts.” The original talk is much better, and I’m glad to find it again.

The core idea has suck with me all this time: that social and technological advances free up people’s time and create a surplus of cognitive and social energy, and then new “products” emerge to soak that surplus up so that people don’t actually use it for anything dangerous or disruptive. Shirky’s two examples are Gin and TV Sitcoms; this has been in my mind more than usual of late as people argue about superhero movies and talk about movies as “escapism” in the exact same terms you’d use to talk about drinking yourself into a stupor.

Something I talk about a lot in my actual day job is “cognitive bandwidth,” largely inspired by this talk; what are we filling our bandwidth with, and how can we use less, how can we create a surplus.

And, in all aspects of our lives, how can we be mindful about what we spend that surplus on.

Tales of the Valiant

In order for this game to make sense, you have to remember why it exists at all. Tales of the Valiant is Kobold Press’ “lawyer-proof” variant of 5th Edition Dungeons & Dragons, created as a response to the absolute trash fire Hasbro caused around the Open Game License and the 5th Edition System Reference Document early last year.

Recall that Hasbro, current owners of Dungeons & Dragons, started making some extremely hinky moves around the future of the OGL—the license under which 3rd party companies can make content compatible with D&D. Coupled with the rumors about the changes being planned for the 2024 update to the game, there was suddenly a strong interest in a version of 5th Edition D&D that was unencumbered by either the OGL or the legal team of the company that makes Monopoly. As such, Kobold Press stepped up to the plate.

Because history happens twice, the first as tragedy, the second as farce, this is actually our second runaround with D&D licensing term shenanigans spawning a new game.

For some context, when 3rd Edition D&D came out back in 2000, in addition to the actual physical books, the core rules were also published in a web document called the System Reference Document, or SRD, which was released under an open source–inspired license called the Open Gaming License, OGL. This was for a couple of reasons, but mostly to provide some legal clarity—and a promise of safe harbor—around the rules and terms and things, many of which were either taken from mythology or had become sort of “common property” of the TTRPG industry as a whole. The upshot was if you followed the license terms, you could use any material from the rules as you saw fit without needing to ask permission or pay anybody, and a whole industry sprung up around making material compatible with or built on top of the game.

When the 4th Edition came out in 2008, the licensing changed such that 3rd party publishers essentially had to choose whether to support 3 or 4, and the rules around 4 were significantly more restrictive. The economy that had grown up under the shade of 3rd edition and the OGL started, rightly, to panic a little bit. Finally, Paizo, who had been the company publishing Dungeon and Dragon magazines under license from Hasbro until just about the same time, stepped up, and essentially republished the 3.5 edition of D&D under the name “Pathfinder.”

There’s a probably apocryphal line from Paizo’s Erik Mona that they chose to create Pathfinder instead of just reprinting 3.5 because “if we’re going to go to the trouble of reprinting the core books we’re going to fix the problems”. (Which has always stuck in my mind because my initial reaction to flipping through the core Pathfinder book the first time was to mutter “wow, we had really different ideas about what the problems were”.) Because Pathfinder wasn’t just a reprint, it was also a collected of tweaks, cleanups, and revisions based on the collected experience of playing the game. There was a joke at the time that it was version “3.75”, but really is was more like “3rd Edition, 2.0”.

When 5th edition came out in 2014, it came with a return to more congenial 3rd edition–style licensing, which reinvigorated the 3rd party publisher world, and also led to an explosion of twitch stream–fueled popularity, and unexpectedly resulted in the most successful period of the game’s history, and now a decade later here we are again, with a different 3rd party publisher producing a new incarnation of a Hasbro game so that the existing ecosystem can continue to operate without lawyers fueled by Monopoly Money coming after them (and yes, pun intended.)

(This isn’t the only project spawned by last January’s OGL mess either; Paizo’s Pathfinder 2 “remaster” was explicitly started to remove any remaining OGL-ed text from the books, it’s not a coincidence that this is when Tweet & Heinsoo chose to kickstart a second edition of 13th Age, the A5E folks are doing their own version of a “lawyer-proof 5th edition.”)

However, Tales of the Valiant had to deal with a couple of challenge that Pathfinder didn’t—primarily, vast chunks of 5E just aren’t in the SRD.