Saturday Linkblog, tiny papers edition

Look at this great collection of very short scientific papers!

I love it when a paper can boil the whole result down to a one or two word abstract, but my favorite is the one about failing to cure writer’s block. Next time I write something with a bibliography, I’m going to find an excuse to cite that one.

Friday linkblog, video game music piano covers edition

Check out this great piano cover of "Erana's Peace” from the first Quest for Glory!

There are maybe a dozen pieces of video game music from the 90s that I’ve had stuck in my head for thirty years now. Mostly bits from LucasArts games: The first two Monkey Islands, TIE Fighter, Sam & max Hit the Road, Full Throttle. But man, that first Quest for Glory was full of music I’m still humming years later, and this was absolutely one of those tracks. Great version!

(Via Laughing Squid)

Premature Quote Sourcing

“Premature Optimization is the Root of all Evil.” — Donald Knuth

That’s a famous phrase! You’ve probably seen that quoted a whole bunch of times. I’ve said it a whole bunch myself. I went down a rabbit hole recently when I started noticing constructions like “usually attributed to Donald Knuth” instead of crediting the professor directly. And, what? I mean, the man said it, right? He’s still alive, this isn’t some bon mot from centuries ago. So I started digging around, and found a whole bunch of places where it was instead attributed to C. A. R. Hoare! (Hoare, of course, is famous for many things but mostly for inventing the null pointer.) What’s the deal?

Digging into the interwebs further, that’s one of those quotes that’s taken on a life of it’s own, and just kinda floats around as a free radical. The kind of line that shows up on inspirational quote lists or tacked on the start of documents, but divorced from their context, like that time Abraham Lincoln said “The problem with internet quotes is that you cannot always depend on their accuracy.”

But, this seems very knowable! Again, we’re talking about literally living history. Digging even further, if people give a source it’s usually Knuth’s 1974 paper “Structured Programming with go to Statements.”

“Structured Programming with go to Statements” is one of those papers that gets referenced a lot but not a lot of people have read, which is too bad, because it’s a great piece of work. It’s shaped like an academic paper, but as “the kids say today”, it’s really an extended shitpost, taking the piss out of both the then-new approach of “Structured Programming”, specifically as discussed in Dijkstra’s “Go to Statement Considered Harmful”, as well as the traditionalist spaghetti-code enthusiasts. It’s several thousand words worth of “everyone needs to calm down and realize you can write good or bad code in any technique” and it’s glorious.

Knuth is fastidious about citations, sometimes to the point of parody, so it seems like we can just check that paper and see if he cites a source?

Fortunately for us, I have a copy! It’s the second entry in Knuth’s essay collection about Literate Programming, which is apparently the sort of thing I keep lying around.

In my copy, the magic phrase appears on page 28. There isn’t a citation anywhere near the line, and considering that chapter has 103 total references that take up 8 pages of endnotes, we can assume he didn’t think he was quoting anyone.

Looking at the line in context makes it clear that it’s an original line. I’ll quote the whole paragraph and the following, with apologies to Professor Knuth:

There is no doubt that the “grail” of efficiency leads to abuse. Programmers waste enormous amounts of time thinking about, or worrying about, the speed of noncritical parts of their programs, and these attempts at efficiency actually have a strong negative impact when debugging and maintenance are considered. We should forget about small efficiencies, about 97% of the time. Premature optimization is the root of all evil.

Yet we should not pass up our opportunities in that critical 3%. Good programmers will not be lulled into complacency by such reasoning, they will be wise to look carefully at the critical code; but only after that code has been identified. It is often a mistake to make a priori judgments about what parts of a program are really critical, since the universal experience of programmers who have been using measurement tools has been that their intuitive guesses fail.

Clearly, it’s a zinger tossed off in the middle of his thought about putting effort in the right place. Seems obviously original to the paper in question. So, why the confused attributions? Seems simple.

With some more digging, it seems that Hoare liked to quote the line a lot, and at some point Knuth forgot it was his own lone and attributed it himself to Hoare. I can’t find a specific case of that on the web, so it may have been in a talk, but that seems to be the root cause of the tangled sourcing.

Thats kind of delightful; imagine having tossed off so many lines like that you don’t even remember which ones were yours!

This sort of feels like the kind of story where you can wrap it up by linking to Lie Bot saying “The end! No moral.”

Except. As a final thought, that warning takes a very different tone when shown in context. It seems like to gets trotted out a lot as an excuse to not do any optimization “right now”; an appeal to authority to follow the “make it work, then make it fast” approach. I’ve used it that way myself, I’m must admit, it’s always easy to argue that it’s still “premature”. But that’s not the meaning. Knuth is saying to focus your efforts, not to waste time with clever hacks that don’t do anything but make maintenance harder, to measure and really know where the problems are before you go fixing them.

What seems to be your boggle, citizen? 30 years of Demolition Man

Sometimes, the best movies are the ones that you find by accident. Demolition Man was one of those.

I distinctly remember there was a mostly-playful rivalry between Demolition Man and Last Action Hero over the course of ’93. Both were the new “big movies” from Schwarzenegger and Stallone—the two biggest action stars of the time—and both were pivoting into the “action comedy” space of the early 90s. (As opposed to the absurdly straight-faced camp the two had been dealing with throughout the 80s.). This had some additional overtones with Arnold operating at a career peak thanks to T2, whereas it had been “a while” since Stalone had a hit.

Last Action Hero, of course, bombed. (To be clear, it’s a bad movie, but the whole middle third in the movie world is better than most people remember, and the joke with Arnold cleaning himself off after he climbs out of the tar pit with only a single paper towel deserves a better movie around it.)

My memory is that Demolition Man didn’t do that well either. The attitude I recall was “well, better than Last Action Hero, anyway”, but not terribly positive. If there was a winner between the two movies, Demolition Man was it, but more by default than anything? (Skimming old reviews, it clearly got some blowback for being “trying to be funny”, action and comedy still not being a common pairing, which considering how the next 30 years went is hilarious. In that respect, at least, the movie doesn’t feel three decades old.)

I didn’t see it in theatres, but it stuck in the back of my mind as “hey, maybe check that out sometime.”

Months later, it found itself, like so many other middlingly successful movies, on constant rotation on cable. (HBO, presumably, but I refuse to go look it up). For some reason, my sister and I found ourselves at home some evening on our own with nothing better to do, and stumbled across it just as it was starting. Sure, let’s give this a whirl for a bit, see if it’s better than the reviews made it sound.

And, of course, it turned out to be great.

It’s an almost perfect early-90s action movie—violent without being too violent, sweary without being too sweary, big explosions, fun action set pieces, jokes that are funny, and a cast that looks like they’re having a great time.

To briefly recap: Sylvester Stallone plays John Spartan, a police officer in the then-near-future of 1996 nicknamed “the demolition man” for the amount of property damage he causes while fighting crime. Westly Snipes is Simon Pheonix, crime lord of near-future LA. Phoenix frames Spartan for the deaths of a building full of civilians during a raid, and the pair of them are sentenced to CryoPrison, where they’re frozen in giant ice tanks to wait out their sentences. (In one of the movie’s many literary references, the CryoCells are frozen instantly something isn't named but is clearly supposed to be ice-nine from Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle.)

Thirty six years in the future, Phoenix escapes from a parole hearing, whereupon Spartan is thawed out to earn an early release by catching his old foe.

The future, meanwhile, is not what either expected, as they find themselves in “San Angeles”, a seemingly utopian combined LA, San Diego, and Santa Barbara, where there’s no real cime, the police don’t enforce anything, swearing is a ticket-able offense, the radio only plays vintage commercials, Otho from Beetlejuice is wearing a mumu, and all restaurants are Taco Bell since the end of the Francise Wars. Because, of course, we’re in one of those “friendly on the surface” dystopias of the THX-1138 / Brave New World mold, where everyone is either trapped in the authoritarian regine with a smile, or eking out a living in the sewers. (Actually, the closest other example I can think of is Doctor Who’s anti-Thatcher scream, “The Happiness Patrol.”)

Spartan is partnered up with a pre-Speed Sandra Bullock’s rookie cop Lenina Huxley (speaking of literary references,) and the two of them track down the mystery of how Phoenix was able to escape and who’s really behind it all.

The action is pretty standard early 90s stuff, mostly real guns with with vaguely science-fictional bits glued on the end, that kind of thing. The centerpiece of the movie is watching both Stalone and Snipes react to the future starting with morbid fascination and ending with open horror than anyone would live like this.

Stalone is always better when he gets to be a little funny, and he does some of his best work in years as John Spartan is constantly wrong-footed by the future while just tying to be an action hero. Sandra Bullock nails both “comic sidekick” and “rookie cop” while hitting the very specific tone of the movie’s jokes (“you can take this job and shovel it”). And Westly Snipes turns in one of the definitive comic book villain performances as Simon Phoenix. The rest of the cast seem to be having a great time, even Denis Leary shows up to be extremely early-90s Denis Leary.

The movies milks a lot of mileage out of Stalone as a fish out of water the “evil utopia” future. The “three seashells” in the bathroom has proven to be the joke with the most pop culture staying power, but for my money the better joke are the ticket printers constantly clattering in the background whenever someone swears. Which feels like a subtle comment on the style of movies at the time?

It’s one of the few movies to try and do future dialect in a convincing way; “enhance you calm,” “what seems to be your boggle?” and the like all elicit a surprised “what did you just say?” reaction while feeling like something that could evolve in the passive agressive dystopia of San Angeles.

Plus, all restaurants are Taco Bell!

It’s aged better than many of its contemporaries , but it’s hard to imagine a plot more wrapped up in the illusory anxieties of the early 90s than the twin pillars of “Gang violence has turned LA into a literal war zone,” and “the worst possible future is if the Politically Correct crowd oppresses the poor libertarians.”

Daniel Waters, who wrote the final script, claims he didn’t have a political angle, but considering we’re talking about the guy who wrote Heathers, you’ll forgive me if I’m skeptical that all that stuff ended up in there by accident.

But, while it still has Dennis Leary show up and deliver the Big Speech About Freedom, it’s a movie with a far more nuanced and ambiguous take on the subject than, say, John Carpenter’s Libertarian Manifesto disguised as Escape from LA. (Although even that movie gets way more interesting when you remember to pair it with They Live, the definitive anti-Reagan movie; but I digress.)

Westly Snipes’ Simon Pheonix has the future’s architect figured out when he calls him an “evil Mister Rogers”; this is a movie that knows that there are worse things out there than wearing mumus and having too many rules. The future’s villains are displaced with comical ease by Phoenix and his gang, and even more critically, the future libertarian resistance proves utterly useless against a real threat. Even the 90s machismo is quietly undercut by Stalone’s knitting.

Instead, the movie ends on a final note of “you dorks all need to relax,” which is probably a moral we could use more of.

But! That all value add; the joy of this movie is in its impish sense of humor as it works through the various action standards.

A favorite example: Towards the end of the movie, Stalone is standing with the now allied rebels and police, all on their way to stop Snipes from waking up the denizens of the CryoPrison.

“Loan me a gun,” he says to Denis Leary’s character, who immediately slaps a revolver in his hand faster than he expects. Without missing a beat, Stalone immediately follows up with “Loan me two guns.”

It didn’t do terribly well in the fall of ’93, but it seems to have been one of those movies that got a real second life on home video. Many, many people seemed to have the same experience I did—stumbling across it, going in with low expectations, and then being delighted to discover something brilliant.

I’m not sure where it lies in the greater Action Movie Canon these days, but I note that everyone I’ve ever talked to about it have fallen cleanly into two camps—folks who don’t remember it at all, and people who love it, a movie that quietly found its people over the years.

It’s a good one.

(And my sister and I still say “Illuminate” whenever we turn on the lights to a room.)

Microsoft buys Activision, gets Zork and Space Quest as a bonus

Well, Microsoft finally got permission to assimilate Activision/Blizzard. Most of the attention has centered around the really big ticket items, Microsoft hanging Candy Crush, WoW, and CoD on the wall next to Minecraft.

But Activision owned and acquired a lot of stuff of the years. Specifically to my interests, they now find themselves the owner of the complete Infocom and Sierra On-Line back catalogs. Andrew Plotkin does a good job laying out the history of how that happened, along with outlining some ways this could go. (Although note that in his history there, the entity called Vivendi had already consumed what was left of Sierra after its misadventures with various french insurance companies.)

I know they’re mostly just looking for hits for the XBox, but Microsoft have found themselves the owners of a huge percentage of 80s and 90s PC gaming. Here’s hoping they do something cool with it all. There has to be some group of Gen-X mid-level managers who want to run with that, right?

Disaster

All of us here at (((Icecano))) have spent the last week horrified by the escalating fractal disaster unfolding in Israel and Gaza.

I don’t have much personally thats useful to contribute, so instead I’ll link to this, from Rabbi Ruttenberg: a lot of things are true.

All our thoughts with everyone in harms way, and hoping they can all find a way out of the storm.

Tuesday Tech Tip: Substack and RSS feeds

TL;DR: every substack has an RSS feed automatically, just put the root of the substack into your feed reader and it works!

With twitter in the final throws of having drunk from the wrong grail, I’ve been retooling my RSS feeds and such. Two years ago my main feeds were my RSS reader and twitter; I hadn’t realized how many RSS feeds had changed location or rotted away since I last did any weeding as most of those folks I also followed on twitter.

Substack seems to be the preferred location for folks looking to stand up a new web presence, and email newsletters are in. And that’s all fine, but my email client is just not where I want to read what we used to call blog posts.

I kept wishing there was an (easy) way to route newsletters to my feed reader, but there’s no obvious UI on substacks around feed locations or RSS subscriptions or anything.

And, I may be the last person on the web to learn this fact, but it turns out all substacks have an RSS feed built right in at /feed. Sane RSS readers will take the root URL of the substack and find it automatically. I guess this is one of those cases where RSS is such a foundational base layer to web tech that it’s one of the “batteries included” and it’s not worth advertising.

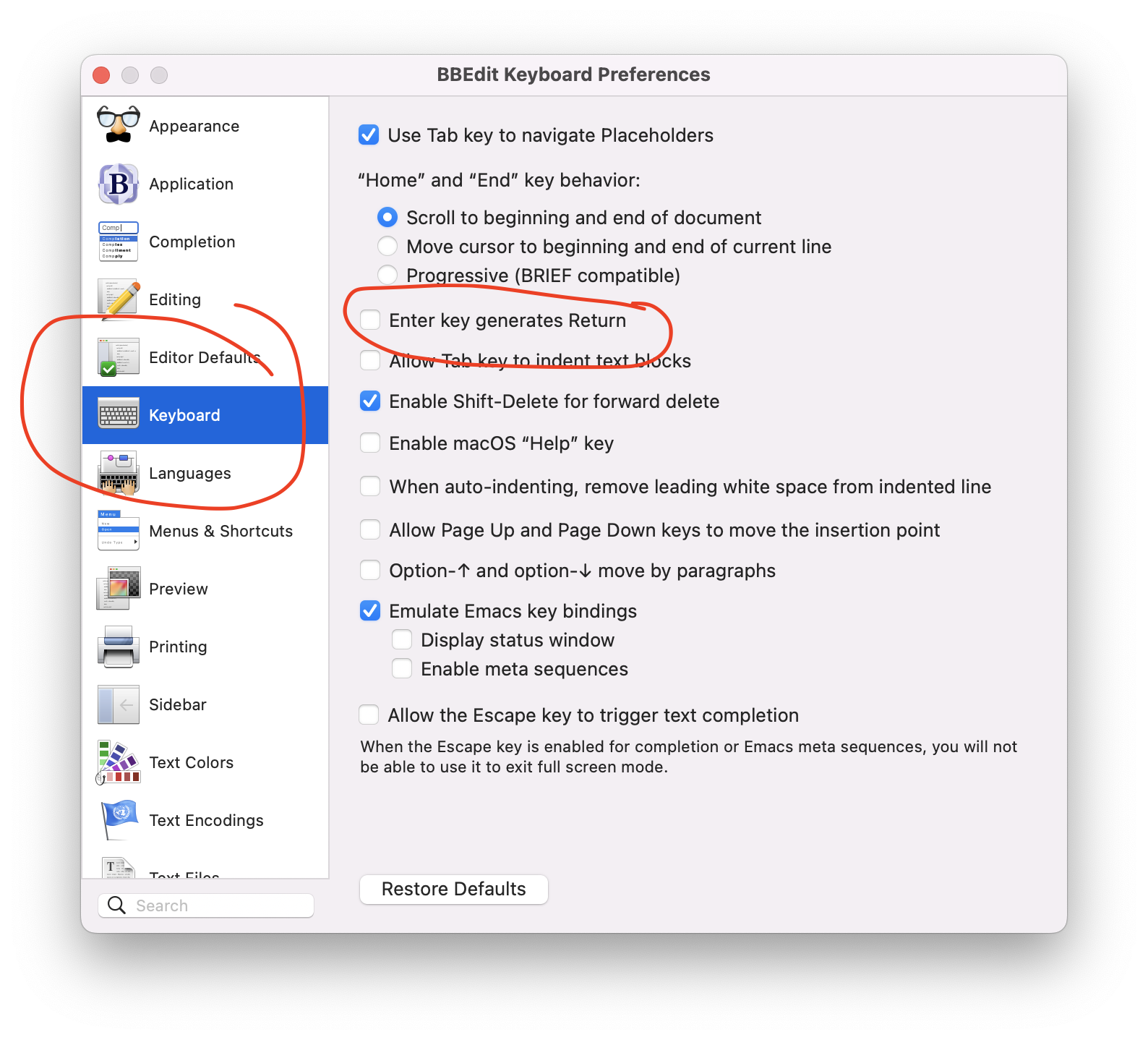

# Monday Tech Tip: BBEdit and using Enter as Return

Like many Mac-weilding software engineers, I edit a lot of text in BBEdit. My main rig has a full width keyboard with the numeric keypad. I tend to use the keypad a lot, since the reality of the day job is that I type a lot of numbers. Something that’s always bugged me about BBEdit specifically is that pressing the Enter key on the keypad doesn’t go to the next line.

Now, on paper—that’s the correct behavior. Return and Enter are, in fact, semantically different, and they’re labeled as such. But, as much fun as “Technically Correct is the best kind of correct” can be, I am not actually entering data into Lotus-1-2-3 in 1986, and as such I don’t really need an Enter key, at least not nearly as much as I need a second Return key over on the far right of the keyboard.

And I don’t know why this took me so long to figure out, because of course BBEdit has a setting for this.

Preferences -> Keyboard -> “Enter key generates Return”

And there you go, perfect, exactly what I wanted.

(And as a bonus, it turns out there’s also an option to make Home and End move to the start and end of the current line instead of the document. Which is absolutely my Windows accent coming through, but I don’t care, that’s how I prefer it.)

With enough money, you don’t have to be good at anything

Following up on our previous coverage, I’ve been enjoying watching the reactions to Isaacson’s book on twitter’s new owner.

My favorite so far has been Dave Karpf’s mastodon live-toot turned substack post. Credit where credit is due, I saw this via a link on One Foot Tsunami, and I’m about to jump on the same quote that both Dave Karpf and Paul Kafasis did:

[Max] Levchin was at a friend’s bachelor pad hanging out with Musk. Some people were playing a high-stakes game of Texas Hold ‘Em. Although Musk was not a card player, he pulled up to the table. “There were all these nerds and sharpsters who were good at memorizing cards and calculating odds,” Levchin says. “Elon just proceeded to go all in on every hand and lose. Then he would buy more chips and double down. Eventually, after losing many hands, he went all in and won. Then he said “Right, fine, I’m done.” It would be a theme in his life: avoid taking chips off the table; keep risking them.

That would turn out to be a good strategy. (page 86)

And, man, that’s just “Masterful gambit, sir”, but meant sincerely.

But this quote is it.. Here’s a guy who found the closest thing to the infinite money cheat in Sim City as exists in real life, and he’s got a fleet of people who think that’s same as being smart. And then finds himself a biographer possessed of such infinite credulity that he can’t tell the difference between being actually good at poker and being someone who found the poker equivalent of typing IDDQD before playing.

With enough money, you don’t have to be good at anything. With infinite lives, you’ll eventually win.

My other favorite piece of recent days is How the Elon Musk biography exposes Walter Isaacson by Elizabeth Lopatto. The subhead sums it up nicely: ” One way to keep Musk’s myth intact is simply not to check things out.”

There’s too much good stuff to pull out a single quote, but it does a great job outlining not only the book’s reflexive responses of “Masterful gambit”, but also the way Isaacson breezes past the labor issues, racism, sexism, transphobia, right-wing turn, or anything vaguely “political”, seeming to treat those things as besides the story. They’re not! That IS the story!

To throw one more elbow at the Steve Jobs book, something that was really funny about it was that Isaacson clearly knew that Jobs had a “reality distortion field” that let him talk people into things, so when Jobs told Isaacson something, Isaacson would go find someone else to corroborate or refute that thing. The problem was, Isaacson would take whatever that other person said as the unvarnished truth, never seeming to notice that he was talking to heavily biased people, like, say, Bill Gates.

With this book, he doesn’t even go that far, just writing down whatever Elno Mork tells him without checking it out, totally looking past the fact that he’s talking to a guy who absolutely loves to just make stuff up all the time.

Like Lopatto points out, this is maddening for many reasons, but not the least of which being that Isaacson has been handed a great story: it turns out the vaunted business techical genius spaceships & cars guy is a jerk whose been dining out on infinite money, a compliant press, and other people’s work for his whole life. “How in the heck did he get this far?” would have been a hell of a book. Unfortunately, the guy with access failed to live up to the moment

The tech/silicon valley-focused press has always had a problem with an enthusiasm for new tech and charismatic tech leaders that trends towards the gullible. Why check things out if this new startup it claiming something you really want to be true? (This isn’t a new problem, I still have the Cue Cat Wired sent me.)

But even more than recent reporting failures like Theranos or the Crypto collapse, Musk’s last year in the wreckage of twitter really seems to be forcing some questions around “Why did you all elevate someone like this for so long? Any why are people still carrying water for him?”

Competing with Patreon

Back in the early ‘00s we spent a lot of time talking about “microtransactions”. This was during the same era we started using phrases like “the long tail.” There was obviously a missing business model somewhere between “selling books” and “subscribing to a newspaper” where people would spend small amounts of money for small things; the example I used to use was we were trying to find the web equivalent of putting 50 cents into a vending machine.

But no one could ever quite figure out how to make it work. Too much friction of too many kinds, and the web fell back on default capitalism model—“free” with ads. And then we know how that turned out, as more VC showed up, we started hearing about growth over everything else, and the business models in the tech world got stranger and stranger.

I don’t personally make money being creative on the web, but I know people who do, or at least used to, and from the outside, Patreon seems like it’s a solid swing at that missing piece we were looking for 20 years ago, a reasonably frictionless way to spend small amounts of money directly to the person making something. But from the outside, it’s notable that two things seem true: 1) everyone uses Patreon because it’s the only game in town for that set of features, and 2) everyone who uses Patreon seems to hate it.

I was therefore absolutely fascinated by Sibylla Bostoniensis’ How to Compete with Patreon. (Via jwz.)

It’s a through description of everything Patreon does and does not do well, written from the perspective of how to build a better system.

The whole thing was eye-opening, but three things really jumped out at me:

First, Credit card fees. I had no idea that Patreon had found a way to essentially round transaction fees to zero, and then… stopped? Like everyone else, I’d love to know what happened there. I’ve worked on more than one project where a features were scrapped once we realized the processor fees would make it unviable, and it’s crazy that someone figured it out and then gave it up. From my position of no inside knowlede, that sure sounds like there was a pile of VC subsidizing the effort that got used up. (How much of the economy of the last two decades was fueled by VC giving away free money rather than any actual coherent economics?)

Second, The techstack. I feel this one in my bones. Modern web frontend javascript frameworks are incredibly heavy, and have a huge list of tradeoffs that need to be carefully considered before you make the plunge into thick client Single Page Apps or the like. Which many many people fail to do, and go with “how it’s done now.” And that would be okay, but so much of “how things are done” come from either Google or Facebook, and just, no one else operates at that scale—nor are they willing to staff at that level.

I’ve had this argument more than one—Sure, Google does it “that way,” but they have a team of 15, and we have 2. Plus, they can pull the plug on any of those features at any moment, because they get all of their revenue from ads, and I guarantee the ad server doesn’t run angular.

And the angle that heavy client-side websites are inherently limiting to your potential audience is a great point that should be made more often.

Third, the cultural mismatch. Not everything is a store! There are business models other than selling a widget at a price (or free with ads.). So many tech bro types don’t have any experience with the worlds where those exist, and want everything to be a neat tidy transition. The description of the conflict over having, essentially, a “pay me now” button is fascinating; if people actually try to defraud their patrons via patreon, that’ll work itself out real, real fast without needing a built in system to guarantee that a package was delivered.

I hope someone takes this description and runs with it. Much like BackerKit realized they were already doing all the hard parts for Kickstarter, so they might as well do the rest of it, I hope someone leans into the space and builds a patreon competitor.

Kirby’s 2001

I need everyone to stop what you’re doing and look at the back cover art from Jack Kirby’s adaptation of 2001: A Space Odyssey.

I like that movie a lot (although I think it’s much more flawed than its fans like to admit,) but I think I would have preferred this version.

Only Victory Laps in the Building

I’m behind in my TV watching, so I’m only just now catching up with the new season of Only Murders in the Building. What an absolute delight of a show; what a joy to watch a cast full of old pros turning out the best work of their careers.

There are a lot of pleasures to this show, not the least of which is finding out that Selena Gomez is the real third Amigo.

But in many ways, it’s a career victory lap for a whole group of comic actors, More creative people should get to do a victory lap like this—not a greatest hits tour, but a final showcase of everything they’ve learned how to do over their careers, a best possible version of everthing they’ve ever done.

(As an aside, the all-time best victory lap is still David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: The Return, which spends 18 episodes moving through a riff on just about every movie he’s ever made with long stops at both Eraserhead and Mulholland Drive, an experimental movie about the atomic bomb, all full of actors he’s worked with before or wanted to ork with and never had a chance to, before turning out a surprisingly satisfying Twin Peaks movie. More people should get one of these.)

While the cast is stuffed full of old pros (Andrea Martin! Nathan Lane! Jane Lynch! Tina Fay!) the centerpiece of course is the pair of Steve Martin and Martin Short.

Both Steve Martin and Martin Short have their respective personas they’ve mostly stuck with over the last 40 years—Steve Martin as a self-important blowhard who’s not nearly as important as he thinks he is, and Martin Short swinging from frantic/neurotic to unhinged. Here, though, they play mostly in the same space, but let their age add some extra notes. Steve Martin plays this particular blowhard with a deep sadness in his eyes, as if he can’t quite muster the energy to keep up the act, but doesn’t have anything else to fall back on.

Martin Short is the absolute standout, though. He does his array of wacky antics and neuroses, but adds a weight to all of it. On the surface, “Oliver Putnam” is a Martin Short character, but weighed down by decades of failure, a character who is just self-aware enough to be unhappy, but not self-aware enough to be able to do anything about it. It’s everything he’s ever done before, but better than you’ve ever seen it, refined to absolute diamond purity. It’s an absolute masterclass in comic acting and character work.

And this year, he manages to take it up even further, more than holding his own against Meryl Streep of all people, conclusively proving how good he’s been all along.

So, hypothetically speaking of course, if a big web outlet whose name rhymed with Plate asked me for a 1500 word hit piece on my choice of the cast of OMITB, for most of them I can kind of see what shape such a hit piece would take. I wouldn’t agree with any of this, mind you, but I can see how you would do it. Steve Martin—“been doing the same schtick for 40 years!” Selena Gomez—“Disney Channel go home!” Nathan Lane—“should have stayed in animation!” Paul Rudd—“go back to ant man!” Even with Meryl Streep you could do something like “let someone else have a turn!” But Martin Short? I wouldn’t even know where to start with that one. He’s always been good in everything. The bad movies he’s been in, and he’s been in quite a few, he’s always the best part. Even Clifford, which might legitimately be the worst movie I’ve ever seen, is the kind of bad that required an actual genius to just completely take the governor off. The thing he does with his face when Charles Groden shouts “look at me like a real human boy!” is pure art.

Anyway. The good news is that everyone has been sharing their favorite Martin Short bits, which mostly means a whole bunch of Jiminy Glick I hadn’t seen. A perfect Martin Short character, deeply weird, very silly, willing to make himself look very stupid, and a masterclass in improv… combat, basically?

The best part about the Glick bits was the way Martin Short was blatantly trying to crack up the people he was interviewing, and he’d just continue escalating until they broke. And I’d love to know what the behind-the-scenes of filming these was like, because when they start the guest always has this stunned look on their face that seems to say “I was just talking to Marty, and then he just turned this on.”

So I’ll take this opportunity to leave you with a couple of my favorites:

Nathan Lane, who tries hard at first to roll with whats happening and then gets completely sideswiped.

Stephen Spielburg, who also does pretty well, until Short hits him with something that cracks up the crew and then just gives up and surrenders to the flow.

Alec Baldwin, who is one of the very few people to manage to wrestle away control and then do his own material for a minute or two, to Short’s obvious delight. A couple big laughs from the crew in this one.

Also, go watch Innerspace.

So long, tiny dancer

We’ll miss you iPhone mini, come back soon

As widely rumored, Apple discontinued the mini-sized iPhone last week. It was my favorite.

I’ve been a (mostly) happy iPhone customer since I saw the original in person over the summer ’07. I’ve never been an “upgrade every year” guy, or even every-other-year; but I’ve ended up with a new one every three or four years as batteries run down and the software baseline outstrips the aging hardware.

My least favorite thing about them is that they’ve gotten so big.

My all-time favorite form factor was the 5s. Bigger than the original, but still easily used in one hand. (And still had the headphone jack!) I loved the flat sides and all-glass front—in my mind, that’s the classic look. The iPhone’s version of the ’67 corvette.

My least favorite, by comparison, was my next phone, the iPhone 8. Too big, too clunky, I deeply disliked the overly thin body and rounded edges. Of course, that design, originally from the 6, ended up as their longest-running design, becoming the soft of default iPhone look for most people.

And they just kept getting bigger. Pros, Maxes. I’ve got decently large male hands, and I found the new ones uncomfortable to use. I like using my phone in one hand, I like keeping it in my pants pocket all day. The larger phones got, the less I could use them like I wanted.

Then, they announced the 12 mini—not only a return to the classic design language, but back to the smaller size! Finally. I pre-ordered it on the day of the announcement, something I had never done before.

The weird thing about it was that this came along with Apple solidifying the iPhones into two sub lines—“regular” and “pro”, with some significant differences between the two around the camera and other features. Each subline got two phones, the standard model, and then the Pros got the frankly obnoxiously large Pro Max, and the non-Pro got the smaller mini. Other than the size the two sizes of each subline were identical—except for the size of the battery, which expanded or contracted to fit the volume available.

And this seemed to trip the whole thing up. There seemed to be a lot of pent-up demand for a smaller phone, but the reality wasn’t quite what anyone expected. I knew more than a few people that that wanted a smaller phone, but weren’t willing to give up the “good” camera. On top of that, the 12 mini had shockingly poor battery life compared to it’s immediate predecessors, and I think it was real easy to sigh and buy the bigger one.

In addition, and uncharacteristically for Apple, the marketing on the mini seemed almost non-existant; it seemed like the original release of the 12 mini flopped, and then they threw up their hands and grudgingly went through with the plans they already had for a 13 mini but no more.

And in a lot of ways, “Mini” was the tell. In Apple-speak, the small-but-good models end with “Air”. Mini was the term they used for the smaller, cheaper iPods; no one thought those were as good as the “regular” iPods, those were the ones you bought because you needed something cheap or needed something really, really small. Everyone I knew with an iPod mini had one as their “other” iPod, they one they jogged with, not the one they ran the party playlist with. But that doesn’t apply to iPhones, you don’t have your “other” iPhone you take jogging.

So, for the 14 models, they replaced the “other non-pro phone” with the 14 Plus, which was a 14 but a little bigger, a phone even less people wanted. Rumor has it that it’s not just the mini, but the all the non-pro phones that have lower-than-expected sales, with the 14 plus having even worse sales than the 13 mini. Apple likes their 2 or 3 year production cycles, it’ll be interesting to see what iPhones 17 look like. Personally, I think a Pro Mini would sell like gangbusters—that’s something you could sell as an iPhone Air, and charge extra for. But I don’t manage a major consumer electronics company.

Faced with the rumors that the mini form factor wasn’t long for this world, I upgraded to a 13 mini earlier this year, the first time I’ve ever done a year-over-year upgrade, and the first time I upgraded to “last year’s” model.

And that’s gonna be it for a while. It’s my absolute favorite size the phone has ever had, and I’ll upgrade to a bigger device over my dead body.

Here’s hoping they bring a small size back before the battery in this one quits working.

Tuesday linkblog, absurd hardware edition

I have just learned about the Mind Killer Dual Distortion pedal from Acorn Amplifiers; let me quote you the copy in full:

Seemingly crafted by the hands of the Kwisatz Haderach, the Mind Killer by Acorn Amplifiers is a dual distortion device that guarantees to deliver total obliteration in the form of huge gain tones to any rig. Featuring two separately stomp-able distortion circuits in series, each with their own bass boost and clipper diode toggle switches, the Mind Killer offers a mélange of stackable crunch tones in a single stompbox.

The two knobs are labeled SPICE and LIFE!! Incredible. They also have a TMA-1 Fuzz which has a truly excellent red light in the center.

Is this the thing that finally pushes me to learn guitar? No, but it’s close.

And, in case you missed it, a Marine was in a training flight in an F-35 over South Carolina this weekend, got into trouble, ejected. The pilot was okay, but the jet was in stealth mode and on autopilot, so now they don’t know where the plane is?

This is the funniest possible way for the 21st century american military to screw up. I am in love with the mental image of a bunch of FBI guys standing around the pilot’s bed in the hospital asking, “So, son, did the plane give you any idea where it was headed next?”

(They have found some debris now, but they had to ask for help looking for it, which is even funnier. Guess those cloaking devices really do work!)

Saturday Night Linkblog, “This has all happened before” edition

There was a phrase I was grasping for while I was being rude about Mitt Romney yesterday, something half remembered from something I’d read over the last few years.

It was this From “Who Goes Nazi?” by Dorothy Thompson, from the August 1941 issue of Harpers Magazine:

Sometimes I think there are direct biological factors at work—a type of education, feeding, and physical training which has produced a new kind of human being with an imbalance in his nature. He has been fed vitamins and filled with energies that are beyond the capacity of his intellect to discipline. He has been treated to forms of education which have released him from inhibitions. His body is vigorous. His mind is childish. His soul has been almost completely neglected.

…

Those who haven’t anything in them to tell them what they like and what they don’t—whether it is breeding, or happiness, or wisdom, or a code, however old-fashioned or however modern, go Nazi.

Haven’t anything in them to tell them what they like and what they don’t.

Friday Linkblog

To quote jwz, “absolute table-flip badassery”: Willingham Sends Fables Into the Public Domain. Cory Doctorow has some nice analysis over at pluralistic.. You love to see it.

Via Kottke, What if our entire national character is a trauma response? We Are Not Just Polarized. We Are Traumatized.. “Before you say “bullshit,” remember: Cynicism is a trauma response.” It’s starting to feel like maybe we’re starting to talk about the effect of ongoing disasters of the last few years, and of the 21st century in general? The weirdest part of living though William Gibson’s Jackpot has been that we collectively pretend it isn’t happening.

Ethical Uncanny Valley

I have never been a fan of Mitt Romney. If you’re looking for a reason, you’re spoiled for choice: beyond his odious-but-generic center-right politics, you have his fortune made by gutting other people’s work, the “binders full of women”, the dog carrier on top of his car, the fact that he was so gutless that his campaign against Obama centered around opposing his own healthcare plan. An empty suit, devoid of an actual point-of-view, whose sales pitch to be president boiled down to “okay America, wouldn’t you rather have a rich white guy again?”

But mostly he seemed to exist in a kind of ethical uncanny valley—too principled to actually go corrupt and join the grift, but not principaled enough to actually work to make things better. Instead, he settled into the role of an ineffectual centrist scold. Not cowardly, exactly, but possessing the demeanor of the kid in elementary school who always reminded the teacher they forgot to assign homework, attempting to score points with a higher authority, without seeming to realize that there isn’t one. Just, jeeze dude, pick a side and get to work.

That said, I absolutely devoured the Atlantic’s except from McKay Coppins’ new book: What Mitt Romney Saw In The Senate.

Sure, It’s clearly trying for reputation laundering, mixed with a final attempt to get some points with whomever he thinks is keeping score, but what struck me the most—if you’ll forgive the technical term—what a giant fucking loser he is.

A man with that much money, who got that close to being president, sitting alone in a apartment he didn’t want, surrounded by art he didn’t chose, eating salmon he doesn’t like slathered in ketchup.

The most revelatory moment for me was a beat where Mitt is struggling over how to vote on the Impeachment, and after expressing this to McConnell, the Senate leader basically says, paraphrasing, “what are you talking about, nerd? He’s obviously guilty, and we’re gonna let him off because we have elections to run.”

A portrait of a suit even emptier than we thought, fundamentally unable to get off the stands and get into the game, so convinced of his superiority that he doesn’t believe in anything at all.

Actually, I take back what I said earlier—he is a coward. He wants points for standing up against Trump and the rest of the party but still won’t, you know, endorse the other guy, or campaign, or take action of any kind besides bitching to the guy writing the book he couldn’t even be bothered to write himself.

What a wasted life. All those people lost their jobs, all those women-in-binders went unhired, all that needless churn, all so one rich, empty white guy could sit alone and watch Ted Lasso, having accomplished nothing. He doesn’t even have the courtesy to want power or influence for its own sake, or to be reaching for self-enrichment—to say nothing of not wanting to make things better—all that sound and fury so he could fill the long, empty, lonely hours feeling smug. All that wealth at the command of a man with no character, no blood, no animus, no soul.

I’d curse his name, but I can’t imagine a worse fate than having to wake up and remember I was Mitt Romney.

Insight-free Doorstop

The Guardian’s Gary Shteyngart calls Walter Isaacson’s new book on Elon Musk an “Insight-free Doorstop”; this is disappointing but not surprising, seeing as that’s how I would have described his book on Steve Jobs.

Isaacson seems to have carved out a niche for himself writing overly-credulous hagiographies of troubling yet successful men. The Jobs book was deeply strange. It was technically clueless, credulous to the point of gullibility, and the good bits were all cribbed directly from Andy Hertzfeld’s Folklore.org. Scene after scene he’d describe something Jobs had done, for pretty obvious reasons, and then Isaacson would throw up his hands as if to say “who can say why anyone does anything?” The second half is even worse, because once he doesn’t have Hertzfeld’s behind-the-scenes material to work from, he just fails to ask any follow up questions, and will either take Job’s word for it, or go get an alternate view from someone like Bill Gates, who is hardly an impartial bystander.

Theres a beat in the middle that’s stuck with me for years. Jobs has just returned to Apple as part of the NEXT acquisition, and is negotiating his return to the CEO role. The board wants to hand him a big pile of stock. Jobs doesn’t want any pay, salary or stock, because he says he doesn’t want to look like he’s just doing it for the money. But the board really wants to give him the stock, because they want him to look like he has some skin in the game. This goes back and forth for a few times, until Jobs says okay, but demands twice as much as they offered him. It’s a classic power move of the kind he makes constantly throughout the book, only doing something if he gets the last word. It’s not that complicated? But Isaacson seems stunned, doesn’t understand why such a thing would happen—and then moves on without even asking about it. This happens again and again. The book walks right up to having an actual insight, gets close enough you can almost do it yourself, but then fails to ask any obvious follow-up questions and then wanders away with a confused head-shake.

He had unprecedented access to a guy who went from being fired by his own company to being the guy who came back and turned it into the most successful company of all time, but doesn’t seem to care to dig in. The book’s analysis of Jobs ends up somewhere around that Dril tweet about drunk driving, effectively saying “well, he was an asshole to everyone, but he also made a lot of money, so, it;s impossible to say if its bad or not,”

The definitive takedown of the Jobs book is John Siracusa’s old Hypercritical podcast where he practically walks the book line by line correcting errors.

In short, it was the kind of book where it looks like he’s being really hard on his subject by writing down things that really happened, all while failing to do any digging or provide any insights that might cause the subject to withdraw their participation. A kind of reputational money-laundering, trying to take credit for being very open and growing, while doing nothing of the sort.

Still, walking back the claims in his own book is a new low.

Newsletter Recommendation: Where’s Your Ed At

I still think it’s weird that in the migration out and away from the Five Websites we seem to have landed on newsletters as the solution?

But! I’ve been meaning to link to Ed Zitron's Where's Your Ed At for a while, but today’s is an absolute barn burner: Elon Musk Is Dangerous To Society.

I’ve been struggling to write something that captures my feelings about the loss of Twitter That Was, but this does a great job summarizing the guy who finished it off.